|

Copyrighted Material -CLICK for information |

|

Back |

|

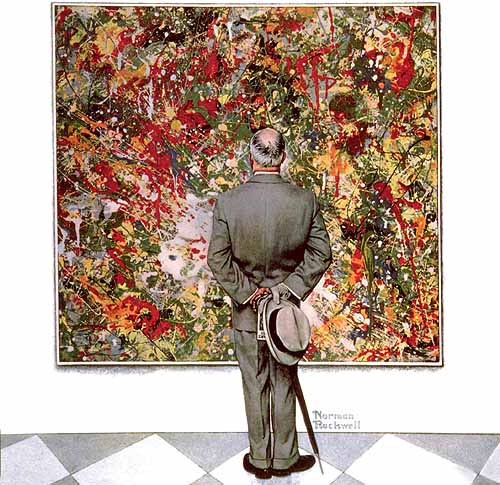

Norman Rockwell, Saturday Everning Post (1962) |

|

The only difference between a fine artist and an illustrator is that the latter can draw,

eats three square meals a day, and can afford to pay for them. -- James Montgomery Flagg |

|

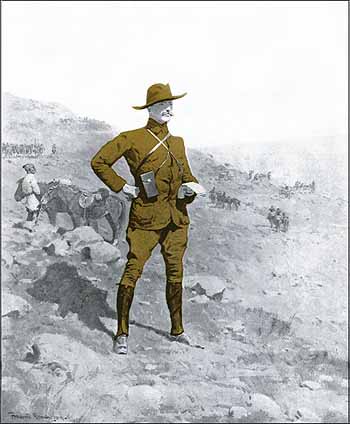

What is "Illustration" and Illustration art, aka "commercial" art is used to embellish, clarify, or decorate something. It can range from a simple black-and-white cartoon to a full-color billboard and beyond. Illustrators in the Golden Age were required to draw and paint expertly and fast. They might be required -- in a few days -- to provide artwork for a battle scene, a love story, a historical drama, a glimpse of the future, and a beautiful American girl. The best of the best commanded top dollar and were as famous as their Hollywood and Broadway pals. Illustration art is also something which has been readily embraced by Joe and Jane America who ordered the illustrator's calendars, asked the magazines for prints, and made scrapbooks of a favorite artist's work. On the other hand, Illustration Art is something that is almost universally rejected by today's art elites, the people who think that if it's obtuse, ugly, or out there, it's art. If not, not. A 2001 review in the Los Angeles Times of an exhibit on Charles Russell and Frederic Remington gave the "elites" their say. The reviewer, who shall remain nameless, went out of his way to: 1) Disparage Russell’s and Remington’s art 2) Disparage the museum for showing this art (not to mention how they showed it) 3) Disparage anyone who went to this show and actually liked this art and worst of all... 4) Disparage anyone so jejune as to emulate this art, especially amateur weekend painters! |

Frederic Remington, Kodak, "The Correspondent" (1904) |

|

I could be wrong, but I’m guessing that Russell and Remington could out-paint, out-sketch, and out-sculpt this reviewer in crushingly superior manner. Yet that's not the point. The point is that this reviewer's opinion is both tediously common among the elites and at odds with what you and I think. I don't blame the reviewer for not liking these artists. No law says he has to. I do blame him for taking the assignment when he was 100% biased against it. And it says a lot that the Los Angeles Times would send a reviewer to cover something he clearly despised. Everyone is biased. I have a bias for GOOD art whether it's at an auction house or in a comic strip. I was raised on popular art and embrace it for its greatness as much as Mozart or Monet. Some random examples as they pop into my head: Alex Raymond, Buster Keaton, The Andy Griffith Show, Pinninfarina, John Barry, Westerns, Jack Kirby, Big Bands, Frank Frazetta, Bill Cosby, Ray Harreyhausen, Chuck Jones, Motown, Frank Capra, Bernard Herrmann, Gil Kane, Supermarionation, Columbo, C S Lewis, Mort Drucker, P J O'Rourke, Walt Disney, Earle Hagen, Jay Ward, Rod Serling, MGM Musicals, Alfred Hitchcock, Steve Martin, Jerry Goldsmith, Stephen Ambrose, and of course, The Simpsons, to name a few. But what do I know? I like Bliss and Bax as much as I like Brahms and Beethoven. I'm not sure Matthew Arnold's high seriousness can be completely blamed that fun and popular art is not to be taken, well, seriously, but surely the buck starts there. And it continues in our current culture. How often does a comedy win the Best Picture Oscar? As of this writing, Annie Hall from 1977 was the last purely comedic film to win (not counting American Beauty which was funny for all the wrong reasons, namely, making fun of everything the elites make fun of already). I remember an acquaintance commenting on a popular comedy, "I like it for what it is." He would have never dreamt of saying that about L'Année dernière à Marienbad. I like serious stuff, too, but I don't like it more than light-hearted fair just because it features a slow-witted, cross-dressing, Vietnam vet (with a drunken NRA father and whoring mom) who likes eating people and/or was the second shooter, Dallas, TX 1963. Frank Tashlin and John Boorman don't make the same kind of art, but they are both competent and creative artists. One makes comedies, one makes dramas. That's the only true difference. |

Willy Pogany, American Weekly, "The Taming of the Shrew" (1950) |

|

One of my college jobs was at a gallery dedicated to new and scalpel-edged art. I remember one artist, Cornelia Breitenbach (1948-1984). Her work was absolutely amazing! I also remember an artist who worked exclusively in lint. Lint. Hey, somebody's gotta do it! Compared to what's been used in "art" since then, lint begins to approach oils and pastels as an acceptable medium. One day, I asked the gallery owner what she thought of Norman Rockwell. "He's quite good," she said, "for what he does. But he's just an illustrator." Just an illustrator. If only he'd had the courage and vision to use the waste from a household appliance. Am I a fuddy-duddy? You bet: a fuddy-duddy for art that takes real skill, real education, real dedication. There are many artists today, illustrator and otherwise who have these traits, but too many non-artists are being hailed as masters, like the fellow who won the Turner Prize for "The Lights Going On and Off" which consisted of -- lights going on and off. Perhaps you'd like to be considered for the Turner Prize. Some suggestions: 1) Diaper Rash No. 9 2) McDonald's wrappers smothering a Barbie 3) The Last Supper re-imagined in nose hair 4) Blue banana: American Imperialism's rape of the Rain Forest 5) Southern Baptist woman eating chicken 6) My laundry, why won't someone do it? 7) Diaper Rash No. 9, one year later |

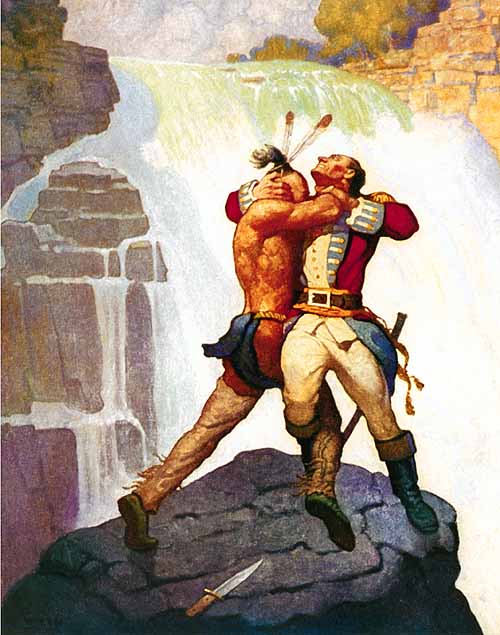

N C Wyeth, "The Last of the Mohicans" (1919) |

|

OK, we know many art elites hate illustration. But why do they hate it? The first reason is capitalism. No matter how rich some people become, the machinery that gets them there -- the system of buying and selling, supply and demand -- is held in contempt. The sweat-of-the brow illustrator who works for a living is therefore inferior to the starry-eyed artiste who suffers, starves, and goes simple (a trifecta!) before death mercifully ends the genius' torment (substance abuse, sexual addiction, and self-mutilation are seen as pluses!) Alas, Remington and Russell are capitalist artists. They didn't just paint for galleries which might have snuck them past the stanchions of acceptability; they also prostituted themselves for The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s. They even did advertising. Could they have been ... Republicans? Remington and Russell may have at one time been starving artists, but their goal was not to remain so. They came to make handsome livings (and made a lot of fans happy). Other artists who accomplished the same feat include N C Wyeth, Howard Pyle, Charles Dana Gibson, Jessie Wilcox Smith, the brothers Leyendecker, Rose O’Neill, Maxfield Parrish, Willy Pogany, Elizabeth Shippen Green, Dean Cornwell, John Lagatta, James Montgomery Flagg, Rolf Armstrong; the list is a long one. |

Ben Stahl, McCann-Erickson, "Does it Belong?" (1949) |

| The Art Directors of McCann-Erickson, Inc., provided this copy for the ad above: Next time somebody asks you, "Does fine art have a place in advertising?" -- show them the John Hancock Life Insurance campaign. Rarely in the history of advertising has a campaign more consistently held to the fine arts level. Rarely has one achieved more favorable recognition for the advertiser. These messages have been hung in schoolrooms, factories, and offices. Reprint requests have run into hundreds of thousands. Statesmen have commended them; citizens have been stirred by them. They have won awards. And they purchased readership at well below average cost for the insurance field. We see a moral in all this. It proves, we think, that everything which has the power to move people has a place in advertising's kit of tools. The art of the cartoon belongs; so does the art of the museum; and so does every form of artistic expression in between. The craft of the art director lies in being able to pick, from his broad workbench of persuasion, the right tool for the job every time. |

|

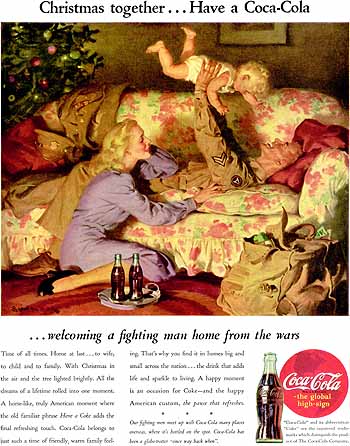

The second reason to hate illustration is its popularity. Popular art is only "art" if you camp it up like Warhol and Lichtenstein. Admittedly, Warhol and Lichtenstein were in it for the cash as much as any illustrator, but they did it the approved money-making way, by taking something the average person likes and mocking it; in the snobs' eyes, that's the legitimate way to make a buck! A third blow against illustration is that it's simply not anti-American. Remington and Russell covered things like soldiers and cowboys and Indians and other John Wayne-ish topics. Other illustrators did those homey magazine covers of happy smiling families (holidays being the most repulsive!), gah-gah couples spooning at sunset (without a mention of global warming), pink-cheeked babes beaming milk-fed smiles, strong men with their hands dirty from farming, ranching, and industry. Don't even get me started about how they showed our men marching off to defend the country and our women rolling up their sleeves to build Mustangs and Shermans and LSTs. The last strike is that there is a spiritual side to a lot of illustration art (and I'm not talking New Age) whether it's for a story or an advertisement, it makes a statement that is unmistakable: good is good and bad is bad. Muddy, gray thinking usually takes a backseat. This clarity is the antithesis of what jazzes the elites. Peter Jennings, being interviewed for his book, In Search of America, said that one of his reasons for writing it was to help America understand that a lot of life isn't as simple as American's think. It's not all black and white. It's mostly shades of gray. I'm sure Jennings meant well, which is why the road to Hell is not known for the quality of its paving. |

Haddon Sundblom; Coke "...welcoming a fighting man home" (1945) |

|

There could be only one valid reason that the elites could claim illustration isn't worthy: it isn't any good. They can't make this claim because it isn't true. They also can't say illustrators weren't good enough to be hung in important venues, because they were! Illustrators' work could be found in museums and magazines, pavilions and posters, all on a given day, and they didn’t save their best for one and short the other. No matter where their art appeared, the artists gave it their best. Al Parker averaged eight paintings a month, each canvas, if he wanted, looking like it was done by a completely different artist, so versatile was the man. In the 40s, with this workload, he was making some $2500 per painting (about $30K now). No venue of the day would pay that kind of money for dreck. So if illustrators were good enough for museums at one time, when did they become unfit? As with most good things, it ended in the 1960s, though the decline started before that. After WWII, illustration was replaced more and more by photography. By the 1960s, illustration was seen as passé and color photography which was new, more immediate, and let's face it, cheaper, took its place. What few illustrators were still around were getting out of the business because business wasn't very good. By the early 1960s, you could buy The Saturday Evening Post and find only one illustration: the cover; all story art was gone. The lament is a greater one because as went the story art, so, too, went the short story, serials, novelizations. Changing tastes, television, and a school system that was beginning its sad decline, brought an end to most monthly and weekly story telling. |

Howard Terpning, "The Professionals" (1966) |

|

And it wasn't too long before book covers and movie posters which once featured the same quality illustrations as ads and slicks, moved to photography and both are the poorer for it. Not only aren't movie posters now being done by illustrators, but movies from the past are having their painted posters ignored when moved to DVD, the art replaced with a dull head shot or uninspired photo montage. Many of the posters being left off the DVDs are justly famous: Frank McCarthy (The Dirty Dozen), Bob Peak (My Fair Lady), Bob McGinnis (Cotton Comes to Harlem), Jack Davis (It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World), Frank Frazetta (After the Fox), Robert McCall (Tora Tora Tora), Saul Bass (Vertigo), Joseph Smith (Silent Running, though the first release had it), John Berkey (The Towering Inferno), William Stout (Caveman), Renato Casaro (Conan The Barbarian), John Solie (Shaft in Africa), John Alvin (Young Frankenstein), Richard Amsel (The Shootist), Drew Struzan (Under Fire), Howard Terpning (The Sound of Music), Reynold Brown (How the West Was Won), Bernie Lettick (Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger), Ted CoConis (Fiddler on the Roof). |

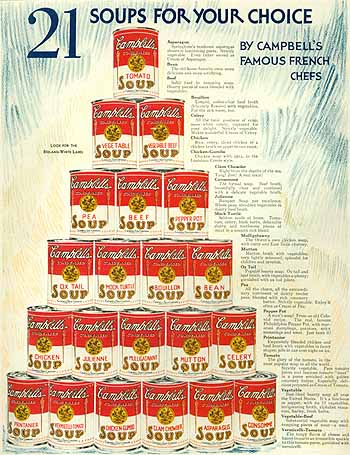

Campbell's Soup (unsigned) (early 1930s) |

|

I suspect illustration art will return to popularity one day as the cycle of photos and non-art for art's sake will run it's course. In the meanwhile, I pity the poo-pooing art elite in the media, academia, and elsewhere. I really do. I can appreciate Herbert Paus as much as I can Jackson Pollock. The elites can't. At least they can't openly without a whiff of irony or a hint of condescension. Just remember that before Warhol made Campbell’s soup cans into his own brand of art, others were doing it on a daily basis, just to sell the soup. |

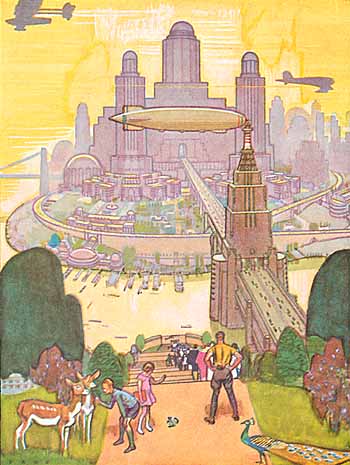

Herbert Paus, "The Future" (1932) |

| Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.

-- Andy Warhol |